Need for a social ecology

At the turn of the 70s, the need for a social and sociological approach to environmentalism and ecologist themes starts to be hardly required.

In those years they happened the first Earth Day in the USA, the first summit on the environment in Stockholm and in 1972 it’s approved the first MIT report on the physical limits of the economical system adopted during the “thirty glorious years”; Unfortunately, one still could not imagine what would happen shortly thereafter with the era of Reaganian hedonism and the illusion of the American dream.

In the USA, this ferment of ideas corresponds to the birth of social ecology, not only in terms of formal discipline but also at the level of collective movement.

Its main focus is on the issue of environmental injustice, in particular on the structural link between social deprivation and exposure to environmental degradation. It is highlighted the western cultural problem: the lack of understanding of the limits of our planet’s carrying capacity, namely the myth of unlimited progress.

Modernity and the myth of progress

Let’s go by degrees: what we mean by the myth of progress and when it comes to manifest itself in its most magnificent light. Evidently, the combination of trust in progress understood as technical development and

the tendency to perfect human nature – is one of the highest and most ambiguous products of the European Enlightenment at the same time.

On the one hand, there are the flourishing of the arts, the expansion of the fields of knowledge and the scientific method, while on the other hand, we have capitalism, the birth of the modern state and the advent of secularized society.

The sacred loses its monopoly of defining patterns of behaviour and the social paradigm, and the reason is asserted as the principle of construction of the real. To put it with Kant, “reason comes out of its minority state”.

The time of progress is the time of modernity. The modernization of society can be understood in different ways depending on the discipline in which it is analyzed: it can be recognized first of all in all the changes which occur in a “traditional” community when it begins a process of industrialization and thus in its study (level of technological, economic, scientific and democratic development).

Secondly, modernization refers to the analysis of the characteristics of the “backward” countries and the problems they encounter in trying to approach the characteristics of modernity peculiar to the countries which are trailing behind it.

It is clear that this conceptualization of progress and development is characteristic of the West and therefore of all the production of knowledge that has had the privilege of being able to stand as the judging eye of world history.

Development and underdevelopment make sense if they are mutually oriented: It is, therefore, easy to observe how the term underdevelopment has always been linked to the stigmatization of it.

The sociological model on social structure contributes to neo-evolutionism, in particular with Talcott Parsons we witness the redefinition of the evolutionary paradigm that aims to study developed and underdeveloped countries, through the corresponding distinction between theories of modernization and theories of dependence, from which different approaches to development emerge.

The globalist tendency in the interpretation of these issues is the most agreeable: criticizes western “development”, highlighting the consequences of Europeanist and colonialist modernity, defending the unsustainability of exponential economic and demographic growth in conditions of limited resources and, above all, allocated in such a way as to impede an effective global trade process.

There is therefore a need for a “post-development” approach to a wider perception of human and social behaviour, including and above all in relation to the surrounding environment.

Ulrich Beck and the risk society

Ulrich Beck’s theory of the Risikogesellschaft – the risk society – comes very close to this vision of the development of society and the globalized world. For Beck, globality means that no country or group can be isolated from another.

With the advent of what he considers to be contemporaneity, second modernity, the nation-state loses its own territorial sovereignty and must leave room for the re-locating of the political sphere to a supranational level.

Post-modernity represents in these terms both a complete rupture with industrial society and also a continuity given by an exasperated reflection on the unwanted consequences of it.

The risk society – our age – is in this sense a process of self-transformation of modernity. In The World Risk Society (1986) Beck argues that in the globalized world the social production of wealth is equivalent to the social production of risk, which becomes the new paradigmatic notion with which to interpret reality.

Risk is first and foremost the anticipation of a catastrophe, always possible but never taking place: as soon as it becomes a real situation then it is already disastrous. Contemporary society is a society characterized by uncertainty because the basic certainties of early modernity are in crisis. At the present, risks are foreseeable, predictable, but not calculable, and therefore the future becomes problematic.

If before modernity the possible threat was natural, in a certain way external because it was not strictly linked to human activity, in the age of the Anthropocene the danger becomes manufactured by the human hand.

Beck considers seven main risk categories: environmental, terrorist, financial, biomedical, military and IT risks. The characterization of risk becomes even more precise if we consider three descriptions which help us to assume it as a matrix of contemporary time

The risk is characterized primarily by relocation since the causes and consequences are not confined to a single location but can be felt anywhere; then it is incalculable, because by definition, as we have just said, risks are never real, but always hypothetical or virtual. Finally, as a direct consequence of the preceding points, the risk is not commensurable: cannot be compensated but can be prevented by precaution.

According to Beck, a global risk society that understands itself can think about itself in three ways: global dangers inevitably establish reciprocity and global exchanges, and thus the contours of a world public sphere begin to take shape.

Secondly, there is a perception of a global self-threat, to which international politics can respond by developing institutions detached from state territory; In the end, therefore, the boundaries of politics linked to the national and state network of a place can be set aside and be over-ridged by the real interdependence of individuals and globalized society.

The ontological struggle against western dualism

Climate change and the worrying prospects of Beck’s environmental risk studies have manifested themselves in several different ways over the last 20 years. Instead, it is now more than a year that the Earth has definitively imposed itself asking for the real need to re-dimension the anthropocentric vision of the human species.

To put it with Latour, “the meaning of living in the age of the Anthropocene is that all agents share the same changing destiny”, therefore it is necessary to change everyone’s habitus of existence. Human being is a species like any other within the natural realm. There can no longer be a clear distinction between the objective and the subjective, between the human and the “natural”, because the human is natural.

Beck’s hope that is to take on the challenge of the contemporary as the interconnection of territories no longer confined to their own state limits would no longer be enough. It is clear that at this level of problem it is necessary to restructuring Western man’s perception of the environment in a broad sense.

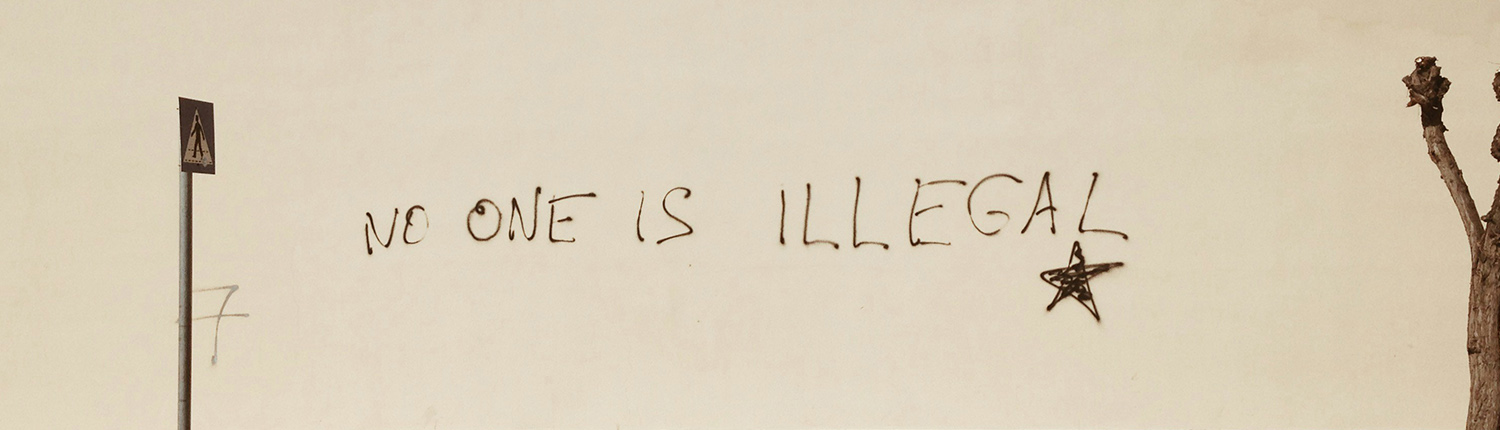

This is why it is no longer possible to obscure the difference and enclose it in anachronistic stereotypes linked to the myth of the good savage. Other cultures that the West has repressed since 1492 can teach us how to take back a caring relationship with our surroundings, the other and ourselves. Let’s give them space.

Bibliography:

KANT, Answering the Question: What Is Enlightenment?

BECK, “The Cosmopolitan Society and Its Enemies”, in Theory, Culture and Society 19 (1-2), 2002.

BECK, World Risk Society and Manufactured Uncertainties, October 2009.

LATOUR, “Agency at the time of the Anthropocene”, in New Literary History vol. 45, pp. 1-18, 2014.

Other bibliographical advice:

- BARREAU, Ora. La più grande sfida della storia dell’umanità., Add Editore, 2020.

- ESCOBAR, “Posconstructivist political ecologies”. In Redclift M., Woodgate G. (eds.). The International Handbook of Environmental Sociology. Second Edition. Cheltenham, pp. 91 – 105, 2010.

Condividi questo articolo

Graduated in Philosophy (Unipd), she is pursuing a Master’s Degree in Philosophical Methodologies (Unige). She is passionate about political philosophy and interested in everything that allows individual and community growth, always been sensitive to issues of social justice. With enthusiasm, she decided to collaborate with Atmosphera lab.