The “gentrification of used goods”

There are several solutions, the first of which would be to decrease production and buy more second-hand clothes. This would curb the exploitation of raw materials and cushion the harmful consequences of producing such a large amount of garments. In addition, buying used clothes would help recover the waste which, instead of ending up in landfills or dispersed in the environment, would be put back into circulation for a longer period of time. This would also help “falling within the environmental costs” given by their production.

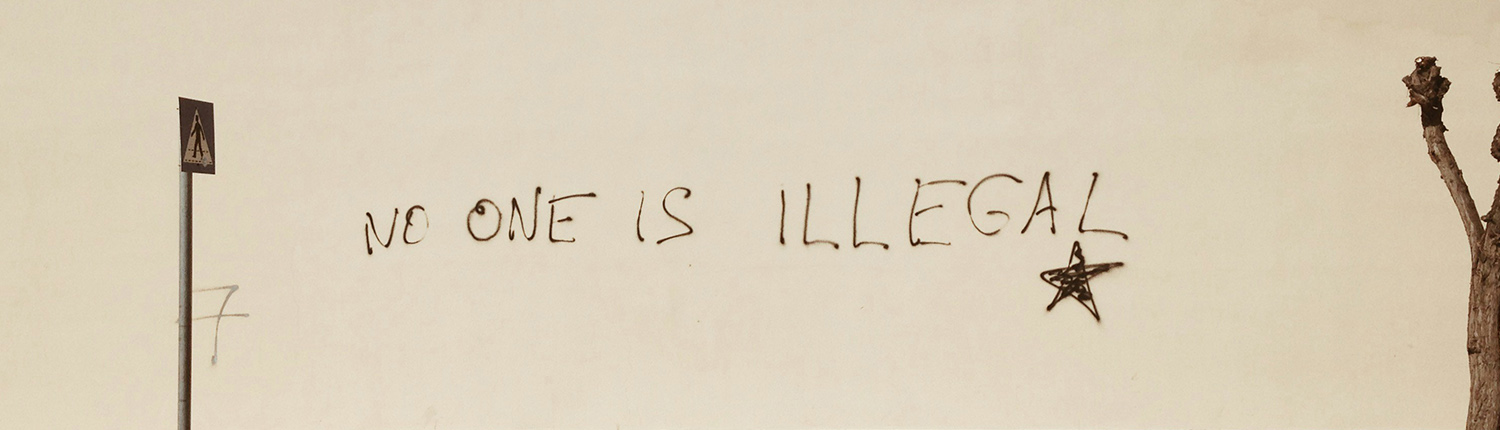

This solution could, however, raise issues regarding the concept of social sustainability: as influencer Giorgia Pagiuca (@ggalaska) pointed out on her platforms, in some cases we could have a “gentrification of used goods”, whereby buying second-hand clothing becomes a fashion statement. This, in addition to being simply perhaps another facet of consumerism, would take away the possibility for those with less financial means to find garments and sizes.

Circular economy

It would be therefore necessary to seek different solutions. One of these is the production of clothes made of regenerated fibers.The core concept comes from circular economy: waste is put back into use and becomes raw material again.

Several Italian companies, including, for example, Rifò Lab and Save the Duck, have taken steps to meet the new demand for sustainable and circular fashion. As a result, various certifications have acquired significance in the textile industry: as far as this article is concerned, especially the Global Recycled Standard (GRS) and the Recycled Claim Standard (RCS).

Promoted by Textile Exchange, a global nonprofit organization that addresses environmental and social sustainability in the textile industry, these certifications guarantee consumers a total of at least 20 percent (GRS) or 5 percent (RCS) of recycled materials, which may come either from post-consumer waste or from pre-consumer waste (i.e. industrial waste).

These certifications trace the entire production chain, promoting lower use of virgin resources and chemicals and high quality recycled materials, while monitoring work ethics and traceability.

To buy less but better

The disadvantage of this option may be the price: such thorough procedures and checks increase costs to such an extent that they cannot compete with those of fast fashion. Therefore it is clear that if a Save the Duck jacket costs five times as much as a Zara jacket, this type of fashion remains a solution only for those who can afford it.

This kind of sustainable fashion, however, would be the key to producing quality clothing and, more importantly, to recovering waste materials that would harm the environment and ecosystems. It could also bring new awareness about work ethics in the fashion world to the consumer and it could help provide a better understanding of what the real consequences of what we produce and wear are.

Besides, it could be a good way to avoid, at least partially, the “gentrification of used goods”: it would make it possible for those who want and those who can to buy sustainably produced clothing, while leaving for those who need it most the option to buy second hand clothes at a lower price. At the same time, it would be an opportunity to rethink our consumption habits, restrain the impulse to buy in large quantities even when it is not needed, and possibly buy durable, high-quality clothes: in short, buy less but better.

Graduated in Journalism, Editorial Culture and Multimedia Communication, she loves travelling and learning about cultures and languages. She is interested in social and environmental justice to raise awareness.