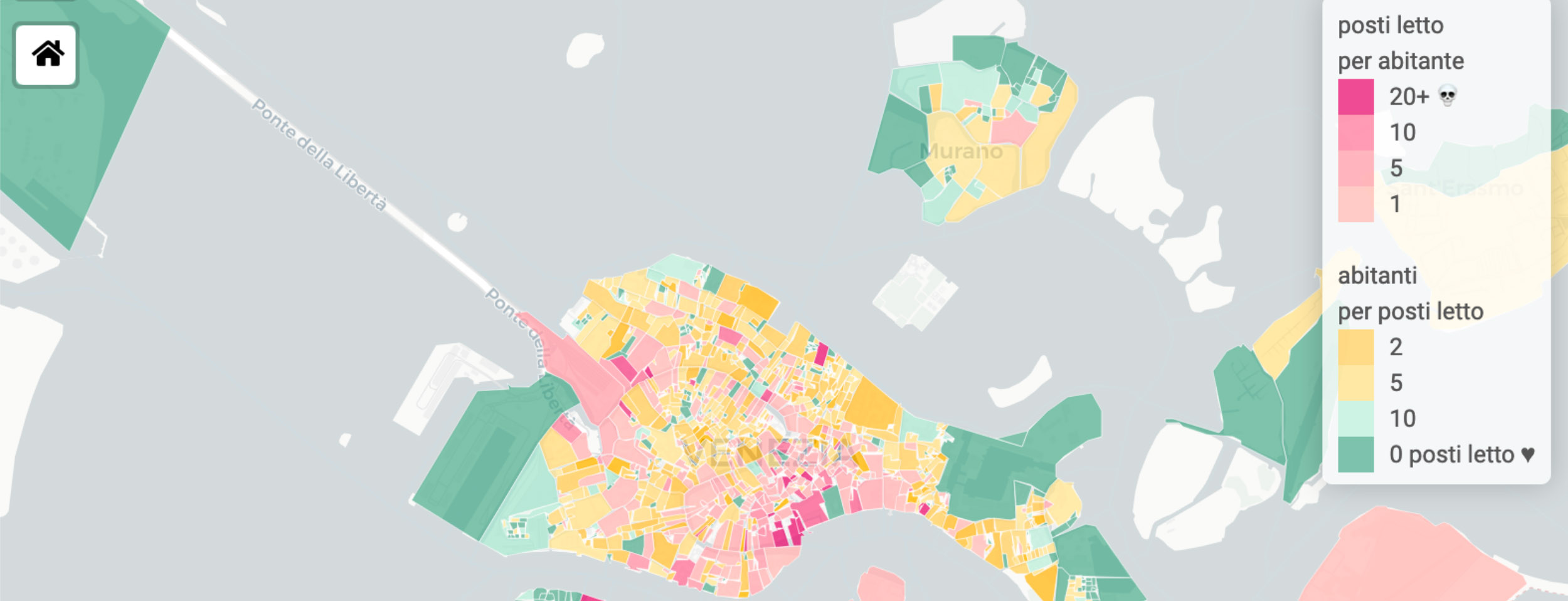

Housing situation Venice 2023, ph. by OCIO

Only a few days later, on September 14, during the UNESCO World Heritage Committee meeting in Riyadh, the Secretariat and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) listed the reasons for the proposal-then unsupported by the members of the intergovernmental assembly-to inscribe Venice and its lagoon on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Among the reasons presented were mass tourism, declining numbers of local residents and inadequate local planning.

In between these two dates, on September 12, the Venice City Council approved a new text regarding the access fee regulation, a rule already provided for in a February 2019 budget law. The introduction of the access “ticket” will be started on an experimental basis from April-May 2024.

How the access fee works

The ticket involves day visitors paying a €5 fee, payment of which can be proven by presenting a QR code, failing which they risk receiving a fine of between €50 and €300. The access fee will be charged only 30 days a year, chosen because of the large influx of tourists expected.

Those exempt from payment, who will still be required to book access, include overnight tourists, residents of the Veneto region, those in need of treatment or participating in sports competitions, law enforcement officers on duty, and relatives of residents up to the third degree. Children under 14, residents of the municipality, workers and students will not have to pay for access or make reservations.

A debated proposal

The introduction of the access fee is a measure designed to disincentivize day tourism and encourage overnight tourism. In fact, according to Tourism Councillor Simone Venturini, such a measure would provide tourists with a higher quality of visit, thanks to greater usability of the various services available to the visitor, and grant residents a better livability of the city.

However, it is necessary to keep in mind that, over a 20-year period, the number of residents in the municipality of Venice has declined by 22,000, while it is estimated that, over the past decade, the number of annual arrivals in the lagoon has increased from 3.7 million to 5.5 million. The access fee does not seem to be able to help reverse this double trend; on the contrary, it could participate in the musealization of the entire city. In fact, paying an access fee in the city contributes to making tourism in Venice increasingly elitist, in line with a trend already observed when one considers that 62% of the beds for tourist use are in 4- or 5-star hotels. This can only fuel the feeling among residents that the city is increasingly turning into a theme park, or a museum city.

In addition, another problematic aspect of the access fee is that there is no cap on arrivals, but only a “daily threshold of tourist arrivals that determines the application of the access fee in the amount exceeding the ordinary one,” as stated in the Regulations provided by the City of Venice. The lack of an upper limit could make it difficult to control the flow of tourists and manage the resources needed to preserve the cultural and natural heritage. This aspect raises many questions about how the ticket will contribute to a better livability of the city.

Finally, although according to the City Council’s estimates the measure is not intended to generate revenue (at least initially), there is still a lack of clarity about the actual uses of the revenue, which is estimated at 1.5 million according to daily arrival quotas. Also according to Venturini’s words, the revenue will go toward paying the costs of introducing the system and then discounting Tari bills to residents. For greater credibility of the measure and a better understanding of its objectives, it is desirable that the financial management plan for the access fee be presented with greater transparency.

To keep living in Venice

Aware that there is no one and only remedy to the problem of mass tourism and the loss of local authenticity in Venice, there is a clear need to avoid simplistic solutions that seem more geared toward supporting a political-administrative agenda than listening to the protests of those who live in Venice and animate it.

The voices of Venetians, amplified by the projects of various collectives and groups including OCIO, Venessia.com, We are here Venice, Venice Calls and Venice urban lab, testify to the difficulties of residing in Venice. They also show that a measure such as the introduction of the access fee is far from effectively responding to the social, environmental and cultural damage that ever-increasing mass tourism is causing to the city.

Matteo Secchi, president of Venessia.com, and Giusi Giudice show the sign announcing the new record (negative) number of residents (Mirco Toniolo / Agf) ph. from La Repubblica

In order to continue living in Venice, we need a housing reform that contributes to the reconstitution of the local social fabric. Building on, for example, the proposed law formulated by Alta tensione abitativa, there is first of all a need to regulate short leases so as to ensure greater availability of space for residents and a brake on rising prices in the housing market.

In addition, it is necessary to return to residents the services that have gradually disappeared, as in the case of Ca’ di Dio, once a nursing home, and Palazzo Donà, formerly home to municipal social services, then used as a luxury hotel.

Finally, it is necessary to think lucidly about the identity of Venice, which is a home for its residents before being a unique destination for those who wish to visit it. It is necessary to allow residents to reappropriate the calli, the campi, the spaces of gathering and community. Not only is “Venice not Disneyland,” as emphasized by the social phenomenon that has made it its slogan, but it is also not an open-air museum. Therefore, only those who inhabit it are responsible for determining its identity.

Student of Environmental Humanities, she is interested in the intersections between culture and ecology. Participate enthusiastically in Atmospheralab.